The Story of USS JUNEAU CL-52 at the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, Her Loss, the Plight of Her Survivors, Their Rescue, and the Legacy of Their Heroism.

by Glenn Smith (USCS 8073)

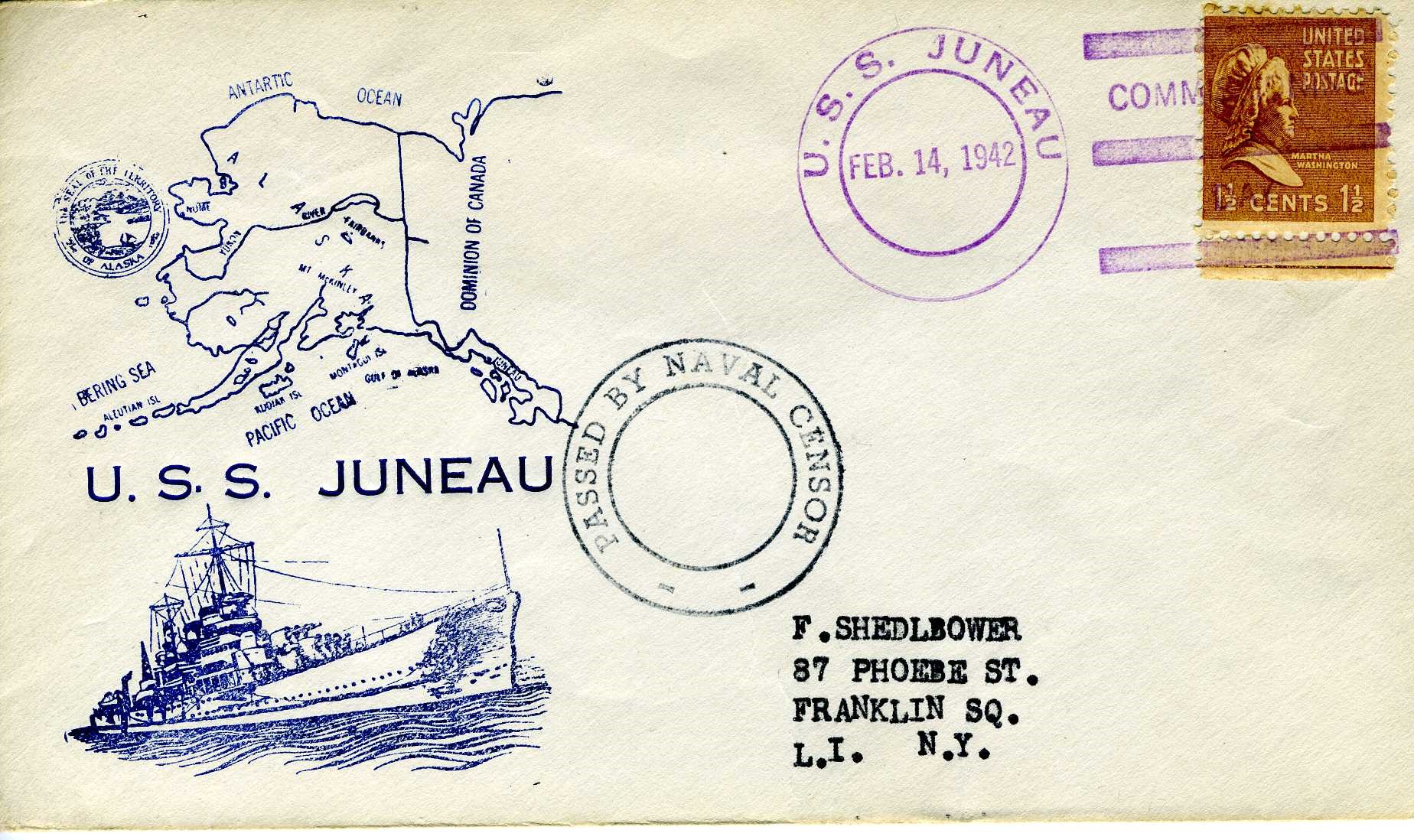

Figure 1: JUNEAU commissioning cover with F (J-11) cancel, marked as passed by censor.

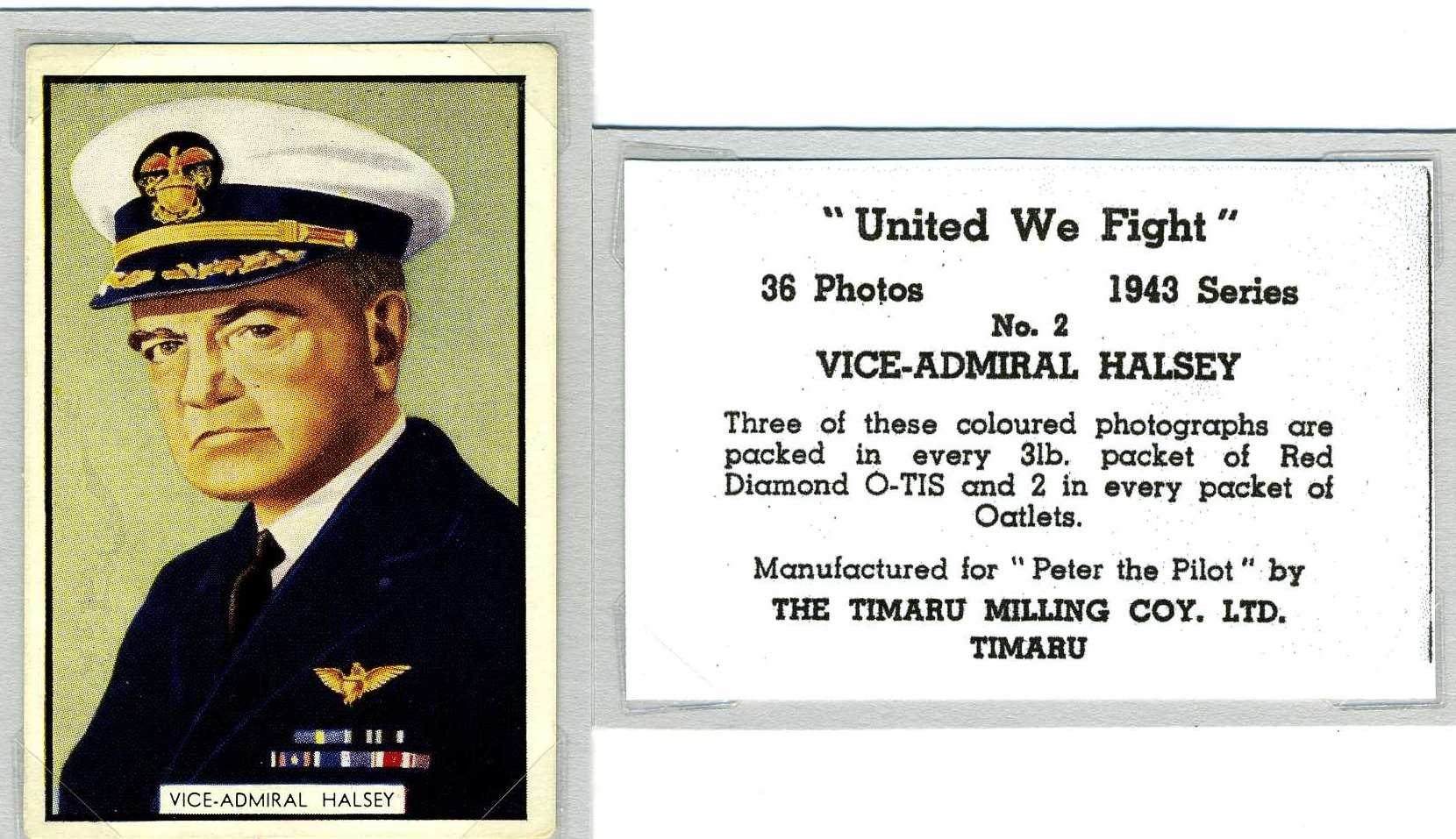

Setting the Stage. November 12th, 1942. On August 7th, 1942, United States Marines landed on Guadalcanal and neighboring Tulagi. It is generally acknowledged that naval support for the Marines was spotty, especially in the early days of their operations ashore. VADM Robert Ghormley, who assumed command of the South Pacific Area in June 1942, was extremely cautious, hoarding his limited resources, much to the chagrin of Marine commanders. By October, Admiral Nimitz, the Pacific Fleet commander, had lost confidence in Ghormley, and sent VADM William F. “Bull” Halsey to relief him. On October 18th, 1942, Halsey assumed command of the South Pacific Area. Changes were swift in coming, and aggression replaced timidity.

Figure 2: Wartime trading card from New Zealand, one of a set that included several notable officers, this one of then VADM Halsey (although his hat brim still shows Captain/Commander “scrambled eggs”). (Front and back.)

In early November, Halsey directed RADM Daniel Callaghan to command a task force (TF 67.4) to protect the landings on Guadalcanal. He was selected to command over RADM Norman Scott, who would now be his subordinate, because he was 15-days senior to Scott. Callaghan had no combat experience, but Scott had just roundly defeated the enemy at the Battle of Cape Esperance (October 11-12, 1942). Callaghan broke his flag in USS SAN FRANCISCO CA-38, and Scott broke his in USS ATLANTA CL-51. Other ships in TF 67.4 were: USS PORTLAND CA-33, USS HELENA CL-50, USS JUNEAU CL-52, USS CUSHING DD-376, USS LAFFEY DD-459, USS STERETT DD-407, USS O’BANNON DD-450, USS AARON WARD DD-483, USS BARTON DD-599, USS MONSSEN DD-436, and USS FLETCHER DD-445.

A Japanese force had been formed to disrupt the landings on Guadalcanal. It consisted of two fast battleships (IJN HIEI, IJN KIRISHIMA)(1), one light cruiser (IJN NAGARA), and 11 destroyers (IJN AKATSUKI, IJN AMATSUKAZE, IJN ASAGUMO, IJN HARUSAME, IJN IKAZUCHI, IJN INAZUMA, IJN MURASAME, IJN SAMIDARE, IJN TERUZUKI, IJN YUDACHI, and IJN YUKIKAZE). The force had three flag officers, VADM Abe Hiroaki in HIEI (commanding), plus RADM Kimura Sumusu in NAGARA, and RADM Takama Tamotsu (2) in ASAGUMO.

A Recipe for Disaster. Midnight, November 13th, 1942. An important fact that would virtually dictate the outcome of coming events was that both Callaghan and Scott chose fly their flags in ships that had older, inferior air search radar systems. The newest SG (Surface Search) radar had been installed cruisers HELENA and JUNEAU (some sources say also in PORTLAND, but there is disagreement on that point), and in destroyers O’BANNON and FLETCHER. Callaghan opted to place HELENA and JUNEAU last in the cruiser column, O’BANNON last in the destroyer van, and FLETCHER dead last in the entire column. Destroyer CUSHING, which was at the point of his column, had no radar.

The Japanese commander, VADM Abe Hiroaki, had deployed his vessels in a complicated, loose circular formation as he approached Savo Island. But his ships had no radar, they had come though heavy squalls, and had become disconnected from each other. YUDACHI and HARUSAME, for example, were “out on a limb” by themselves. Abe’s battleships were prepared for night bombardment of Guadalcanal, and initially had anti-personnel rounds in their big guns. When the enemy was discovered, both battleships had to quickly reload with armor-piercing shells, and they lost precious time in the process.

Figure 3: Opponents at Initial Contact, about 0130, November 13th, 1945. Drawing by author.

A Bar Room Brawl with the Lights Shot Out. 0130-0300, Friday, November 13th, 1942. Both forces charged through the night, Abe blind without radar and overly confident that his vaunted lookouts could pierce the night with better vision devices. Callaghan and Scott considerably reduced the advantage that their radar gave them by placing it in the least effective place in the formation. Shortly after 0130, CUSHING had to come hard to port to avoid slamming into YUDACHI. Then all hell broke loose. The American column initially followed CUSHING’s lead, taking the van destroyers directly toward the enemy battleships. One participant later characterized the resulting melee as a “bar room brawl with the lights shot out.” For the next 90 minutes, ships on both sides fired indiscriminately; sometimes at the enemy, sometimes at friends, and frequently at point-blank range. Torpedoes from both sides filled the waters. Searchlights probed the darkness. SAN FRANCISCO blasted ATLANTA, that fact was established the next morning by the dye on ATLANTA’s deck which matched the dye color used by her big sister’s 8”guns for spotting the fall of rounds. Other highlights of the brawl found LAFFEY engaging battleship HIEI at a range that some put at 75 feet! HIEI could not lower her 14” guns to bear, and LAFFEY peppered her with smaller caliber guns and fled into the night. The action devolved into a series of one-on-one battles. BARTON took on AMATSUKAZE in a torpedo match, and lost, sinking literally in seconds and taking with her 90% of the crew. MONSSEN’s CO, thinking he was receiving friendly fire, turned on his recognition lights…a fatal mistake. All of the enemy guns within sight focused on MONSSEN, making her hull look like Swiss cheese, she sank later in the day. FLETCHER slipped through the ruckus, using her SG radar, launching torpedoes at targets of opportunity, firing 5” guns at multiple targets, and emerged as the only American ship that was totally unscathed. Both Admirals Callaghan and Scott were killed early on at their battle stations in SAN FRANCISCO and ATLANTA, respectively. Command devolved to the next senior officer, CAPT Gilbert Hoover in HELENA, although he did not know that fact until dawn. By 0300, both sides had had enough. Abe and his battleships retired northwest putting Savo Island between himself and his enemy. The American force was scattered. ATLANTA, BARTON, MONSSEN, LAFFEY, and CUSHING would be lost when the smoke had cleared. The enemy had lost YUDACHI, and HIEI would be unable to successfully flee aerial bombers the next day.

The focus of this story, JUNEAU, limped away from the fray, her back broken by a torpedo. PORTLAND was crippled by her rudder being stuck in one position, leaving her making circles. AARON WARD was adrift. By dawn, CAPT Hoover had gathered his remaining cruisers, SAN FRANCISCO, HELENA, and JUNEAU, plus destroyers STERETT, O’BANNON, AND FLETCHER. CAPT Lyman K. Swenson in JUNEAU reported that his keel was so badly damaged that he could not maintain formation, and was allowed to steam independently within sight of the other two cruisers. However, JUNEAU’s damage limited the speed of the entire formation.

JUNEAU’s Fatal Blow. 1100, Friday the 13th, November 1942. CDR Yokota Minoru, commanding submarine IJN I-26, was one of Japan’s most capable submarine officers, and he was on the hunt. He assumed that the action of the early hours of Friday the 13th would leave some juicy targets for him to practice his craft upon. His most fervent hopes were realized when his periscope found SAN FRANCISCO in the crosshairs. As many as six Long Lance torpedoes were sent speeding away from I-26. Observers reported at least two fish passed ahead of SAN FRANCISCO, and one just missed astern of HELENA. The first one to miss also passed ahead of JUNEAU. And then her luck ran out, the second crashed into JUNEAU on her port side, likely hitting a magazine. Many witnesses said the same thing…JUNEAU simply disappeared, vaporized in an instant. A signalman in HELENA was receiving a semaphore message from one of his peers in JUNEAU at the moment of impact. The JUNEAU signalman was thrown about 30 feet into the air as his HELENA colleague watched in horror. No one who witnessed the explosion could believe there would be any survivors. The belief was that 695 men had just perished. Not all had. About 140 men made it into the water.

The Five Sullivan Brothers and others. In JUNEAU’s crew were five brothers from Waterloo, Iowa. Joseph (Red), Francis (Frank), Albert, Madison (Matt), and George Sullivan joined the Navy together and asked to serve together. They were not the only set of brothers in JUNEAU. The four Rogers brothers of Darien, Connecticut were in the commissioning crew. Fortunately for their mother, two (Joseph and James) left just before November 13th, 1942, leaving Louis and Patrick Rogers to go down with JUNEAU. George and Albert Sullivan are known to have survived and make it into the water. Albert succumbed shortly afterward, but elder brother George lingered for several days, and was frequently heard to be calling his brother’s names. Probably hallucinating, George eventually slipped away and was seen to be devoured by circling sharks.

Figure 4: Sullivan Brothers on Marshall Islands #787i of 2001. .

A Communications Fiasco. CAPT Hoover had personally witnessed the explosion of JUNEAU. He had little doubt that all-hands had been lost. His primary concern was protecting his remaining ships from lurking submarines, and so he reluctantly moved his remaining ships away from the scene of JUNEAU’s demise. FLETCHER sought permission to look for survivors, but she was Hoover’s only fully operational destroyer, so she was ordered into a protective screen around SAN FRANCISCO and HELENA. Hoover sent a message by blinker to a passing Army B-17, asking it to relay the last position of JUNEAU to naval authorities. It did not. Another Army B-17, this one piloted by 1stLt Robert Gill, sighted what he thought were about 150 men in the water. He reported the sighting to an Army intelligence officer on Espiritu Santo who made a note of it and filed the report in his desk drawer. Gill reported the sightings to the same officer again on the 15th and 18th. Gill’s observations never reached proper naval officers. On November 14th, VADM Halsey, having received reports of the catastrophic events of the morning of Friday the 13th, sent the following message to all fleet units: “MAGNIFICANTLY DONE X TO THE GLORIOUS DEAD: HAIL HEROES, REST WITH GOD – HALSEY.” What he did not know, was at that very moment, about 140 JUNEAU men were in a life and death struggle with the elements, sharks, and time.

Life and Death in the Water. For up to eight days, JUNEAU survivors fought to stay afloat and alive. Exhaustion, lack of water, and sharks took a steady toll. No search was initiated until a Navy PBY piloted by LT Laurence B. Williamson of Patrol Squadron VP-72 sighted men in the water at twilight of November 18th. Low on fuel, he had to return to base at that point, but he launched at first light on the 19th to search for the men he had spotted. Ten hours into his flight, and again low on fuel, he again sighted the men. Base radioed him that USS BALLARD AVD-10 was enroute, ETA 2300. Williamson knew that some of these men could not last that long, and fully recognizing the risks of landing in rough seas, took his lumbering flying boat into an open seas landing. His daring saved six men. BALLARD later saved one more. Three men made it to a small island and were later picked up by a PBY. Of the 140 or so men that made it into the water, only ten survived. (3)

Figure 5: PBY of the type flown by LT Williamson.

Aftermath. If you simply look at ships lost and damaged, the Japanese won a clear victory. On the other hand, Abe’s mission of bombarding Guadalcanal was stopped, and the havoc that his two battleships would have inflicted on the Marines was prevented. IJN HIEI was lost the next day, and IJN KIRISHIMA would fall to the big guns of USS WASHINGTON BB-56 in the early hours of November 15th, 1942. The Army officer who failed to report men in the water was fired. CAPT Hoover was summarily relieved of command of HELENA by Halsey, censured by Admiral Nimitz, and never again served in a command-at-sea position. Halsey’s failure to launch a timely search for JUNEAU survivors resulted in no discipline for Halsey and became a minor blemish on his record in the history books. It paled in comparison to Halsey’s failure to protect San Bernardino Strait in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, or to properly prepare his ships for typhoon Cobra of December1944. After the war, CDR Yokota became a schoolteacher, changed his name to Hasegawa, and led a peaceful, productive Christian life.

Legacy. A number of ships have been named for the officers and men who participated in the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. Among them: LYMAN K. SWENSON, two THE SULLIVANS, CASSIN YOUNG, NORMAN SCOTT, SCOTT, two CALLAGHANs, BLUE, GEARING, SUTTON, and OBERRENDER. Many of the ships that fought there have had new ships carry their name, including two JUNEAUs (CLAA-119 & LPD-10).

The Survivors. They were:

- Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Charles Wang

- Chief Gunner’s Mate George Mantere

- Signalman First Class Lester E. Zook

- Machinist’s Mate Second Class Henry J. Gardner

- Signalman Second Class Joseph P. F. Hartney

- Seaman First Class Arthur Friend

- Seaman Second Class Wyatt B. Butterfield

- Seaman Second Class Frank A. Holmgren

- Seaman Second Class Victor James (Jimmy) Fitzgerald

- Seaman Second Class Allen C. Heyn

As of July, 2008, only Frank Holmgren remains. There is a nice memorial web site for JUNEAU at: http://www.rtcol.com/~oakland/rostju52.html

Notes:

- Japanese ships are identified as IJN (Imperial Japanese Navy). Some sources use HIJMS (His Imperial Japanese Majesty’s Ship).

- Japanese names use the custom of their culture, with family names first, followed by given names.

- Fate dictated that there would be four additional survivors. SAN FRANCISCO had so many wounded that a call went out for help from other ship’s medical staffs. LT Roger O’Neill, MC, USN, and Pharmacist’s Mates Orrel G. Cecil, Theodore Merchant, and William Turner were transferred by boat from JUNEAU to SAN FRANCISCO on the morning of Friday the 13th, November 1942.

References used:

- Guadalcanal-Decision at Sea, Eric Hammel, 1988, Crown Publishers, NY, NY

- Battle History of The Imperial Japanese Navy, 1941-1945, Paul S. Dull, 1978, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis

- The Campaign for Guadalcanal, Jack Coggins, 1972, Doubleday & Co., Garden City, NY

- Left to Die-The Tragedy of the USS Juneau, Dan Kurzman, 1994, Pocket Books, NY

- USCS Catalog

- Wikipedia